Rising high above the Earth, the Himalayas are not only stunning but vital to geological research. A 2023 study indicates that the Indian tectonic plate, forming the Himalayas' foundation, might be splitting apart due to a unique geological phenomenon.

The Great Himalayas, with their jagged peaks, encompass hundreds of mountains, including the towering Mount Everest at 29,035 feet. Around 40-50 million years ago, the Indian Plate's collision with the Eurasian Plate caused the Earth's crust to buckle, forming these massive structures. Their similar thickness led them to merge rather than crash, resulting in today's colossal formations.

Source: © Michel Royon / Wikimedia Commons

Source: © Michel Royon / Wikimedia CommonsThe Annapurna range of the Himalayas

Stanford geologist Simon L. Klemperer and his team ventured to Bhutan's Himalayas to investigate helium levels in Tibetan springs. Although the region is rich in gold and silver, the unusual helium readings pointed to a possible dormant volcano beneath the surface.

The research explored two theories: the Indian Plate colliding horizontally with the Eurasian Plate, and the Indian Plate dipping underneath, melting into magma and releasing helium. Klemperer's team discovered higher helium levels in southern Tibet than in northern Tibet, concluding that the Indian Plate is splitting into two fragments beneath the Tibetan plateau, a process known as "delamination."

Source: Sanjay Hona / Unsplash

Source: Sanjay Hona / UnsplashMardi Himal Base Camp, Lumle, Nepal

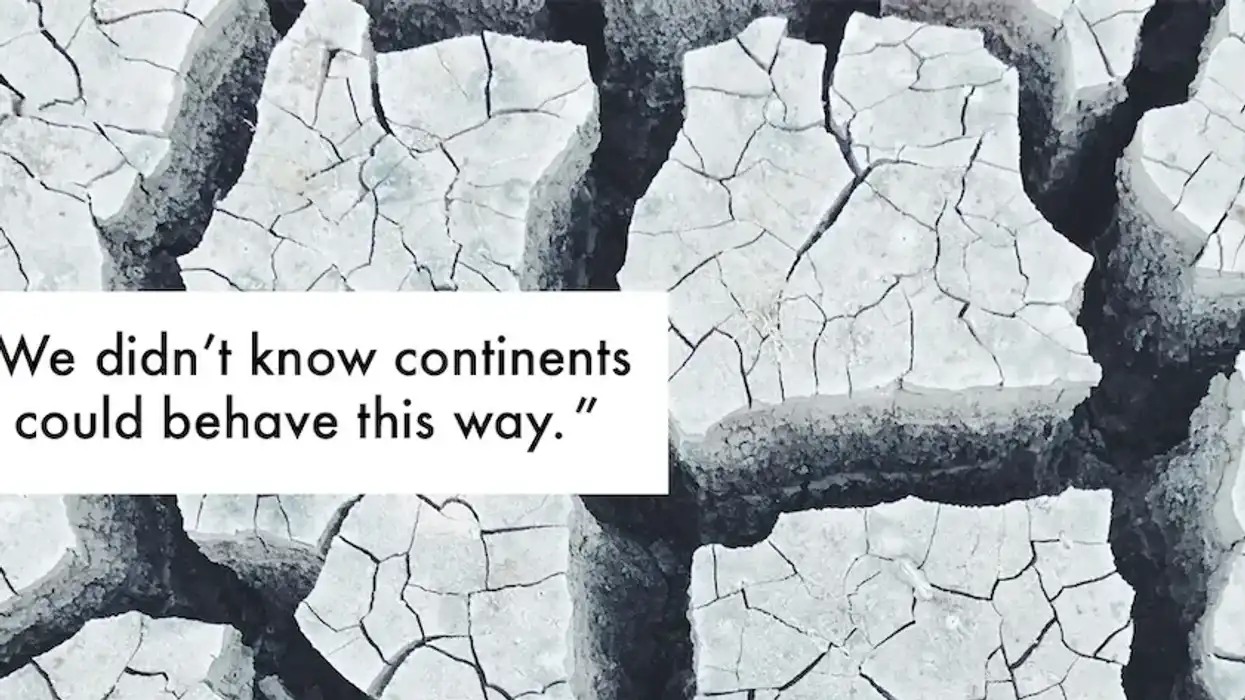

Klemperer introduced a third theory, suggesting both processes were occurring at once: the Indian Plate's top was rubbing against the Eurasian Plate, while its bottom was subducting into the mantle. The findings, presented at the December 2023 American Geophysical Union conference, were groundbreaking. “We didn’t know continents could behave this way and that is, for solid earth science, pretty fundamental,” Douwe van Hinsbergen, a geodynamicist from Utrecht University, told Science.

Using isotope instruments, Klemperer measured helium bubbling in mountain springs, collecting samples from roughly 200 springs over 621 miles. They identified a stark boundary where mantle rocks met crust rocks and found three springs where the Indian Plate seemed to peel like banana skins.

Source: kabita Darlami / Unsplash

Source: kabita Darlami / UnsplashMount Everest, Nepal

Tectonic plates resemble a layered cake, with a dense, thick bottom layer. When plates collide, weaker layers can fracture. Scientists knew plates could peel away like this, mainly in thick continental plates and computer simulations. “This is the first time that … it’s been caught in the act in a downgoing plate,” van Hinsbergen said.

This unstable configuration of tectonic plates threatens the mountain range and indicates potential earthquakes and tremors. While the study provided valuable data, it also highlighted the conflicting forces of nature at work.

This article originally appeared last year.

This represents the key to the perfect flow statePhoto by

This represents the key to the perfect flow statePhoto by

Representative Image Source: Unsplash | Pawel Czerwinski

Representative Image Source: Unsplash | Pawel Czerwinski

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay