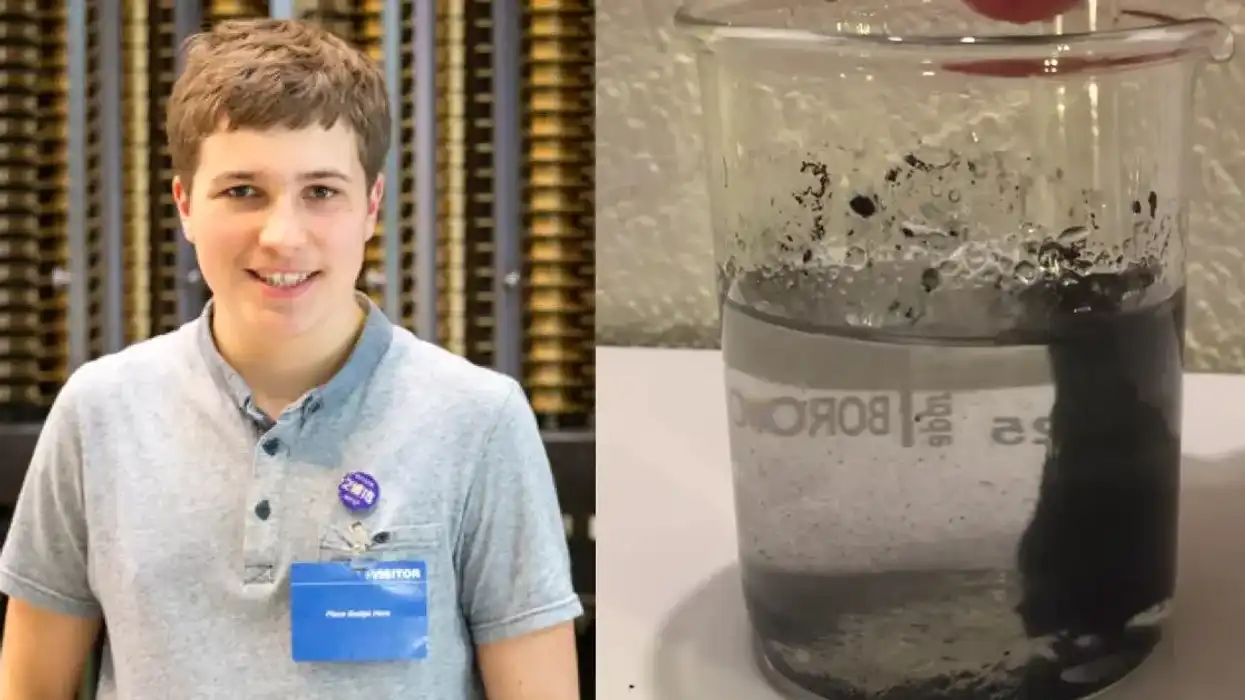

Microplastics are a huge issue plaguing our oceans — but at the same time, they're too small to easily remove from the water. However, 18-year-old scientist Fionn Ferreira may have discovered the solution for that. The West Cork, Ireland native won the Grand Prize at the Google Science Fair for coming up with a pretty genius way to take microplastics out of the ocean.

As explained in Ferreira's report on the Google Science Fair's website, Ferreira's project started when he read a paper by Dr. Arden Warner, who discovered that magnetite powder (aka iron oxide) could clean up oil spills, because the oil and magnetite powder are both non-polar. It gave Ferreira the idea to apply that idea to microplastics in water. So, he threw together a small test at home, and it worked.

"I used this method in the extraction of microplastics by adding oil to a suspension containing a known concentration of microplastics, these then migrated into the oil phase," Ferreira wrote in his paper. "Magnetite powder was added. The resulting microplastic containing ferro-fluid was removed using strong magnets."

Ferreira set out to scale up his experiment, even though he did not have access to a fancy laboratory or team of researchers. "I want to encourage others by saying you don't have to test everything in a professional lab," Ferreira told CNN. "That's why I built my own equipment."

As Ferreira explained in his Google Science Fair entry video, he went on to choose 10 different kinds of plastics to continue testing with, and he conducted more than 1,000 experiments. Eventually, he was able to conclude that his method would effectively be able to remove 85 percent of microplastics from water.

Microplastics are pieces of plastic debris that are five millimeters in length (about the size of a sesame seed) or smaller. Many microplastics come from larger plastic that is in the ocean (most of which is from discarded fishing nets and gear, but also from landfills and litter), which does not biodegrade — instead, it breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces, until it is eventually tons of tiny micrplastics.

Many microplastics are also microfibers, which are tiny pieces of synthetic fibers that enter the oceans when we do laundry. Clothing made from synthetic fibers (such as polyester and nylon) sheds microfibers in the washing machine, which then enter waterways and eventually funnel out to the ocean.

The microplastic pollution problem is so serious that marine life in the deepest trenches of the oceanwere discovered to have microplastic in their bodies. Plus, these microplastics are also polluting human bodies —a recent study found that humans swallow up to 2,000 microplastics every week.

Grand Prize winner at @googlescifair Fionn Ferreira devised a system that removes microplastics from water using non-toxic iron oxide. He was able to pull 85% of 10 different types of microplastics out of the water. Read about all the winners here: https://t.co/sT71a0MRP8 pic.twitter.com/c62vk3WLJa

— Scientific American (@sciam) July 29, 2019

As Ferreira said in his entry video, his next step will be to look into ways to scale his solution up to larger bodies of water so that it could eventually be used on a massive scale. His $50,000 prize from winning the Google Science Fair certainly could have helped with that, but he tells CNN that the money will be going towards his college tuition.

He is heading to the Netherlands this fall to study at the University of Groningen's Stratingh Institute for Chemistry. Hopefully Ferreira's studies will help him further improve this invention, and we will see it implemented in oceans one day in the near future.

Editor's Note: The article was originally published last year.

This represents the key to the perfect flow statePhoto by

This represents the key to the perfect flow statePhoto by

Representative Image Source: Unsplash | Pawel Czerwinski

Representative Image Source: Unsplash | Pawel Czerwinski

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay